Cooking class!

|

| My formal education about Malaysian cooking begins here, at a market in Damansara, on Kuala Lumpur's east side. |

|

| This cannot be happening. |

Luckily, two fellow students are blessed with easy good manners, charm and intelligence, and I immediately bond with them. Kumar is a professional Indian chef in Kuala Lumpur, and Liwen works at a cooking school in Taipei. That afternoon, the three of us will share the same block of four cooking stations, along with Greg, a goofy Taiwanese guy who's seems like he's on another planet. Meantime, my four nemeses will be standing at the four stovetops behind me. I will have literally turned my back on them.

But first things first. At 8 a.m. we all meet up at a market in Damansara, where we are greeted by Zeera, a funny, lovely hostess who grew up in Ipoh. We have a light breakfast of Indian puri and a variety of curries, including a hot white curry (who knew?), and we walk around the market, sampling the sweets and fruits, poking the fish and chatting up the vendors. What follows is a kind of lengthy discussion of Malaysian spices ― feel free to skip; it's important to me. At the beginning of the video, Zeera's in the middle of talking about galangal, one of the ingredients I was pondering at Big Tree Foot when I was trying to figure out what lent citrusy bitterness to laksa. It's all beginning to come together. Spices discussed are:

Galangal

Turmeric (root and leaf)

Kafir lime leaf

Curry leaf

Lemongrass

Laksa leaf (Vietnamese coriander)

Torch flower

Pandan leaf

At the Damansara market, little kids wait for their morning puri.

I used to be freaked out by rambutan because of its spiky rind, but it's super-easy to peel by hand and tastes kinda like canned peaches. Yum.

We pile into a van and are driven to the cooking house in a kampong (village) at the edge of the city, where we are greeted by Irene, the heart and soul of LaZat Cooking. It is from her that I learn the conceptual underpinnings of cooking Malaysian-style ― 1) the importance of flame control (low and slow), 2) the importance of using cooking oil, because no other agent can produce the aromas you seek in as timely a manner and 3) something that surprised me ― the Malaysian chef works as silently (and gently) as possible. If bits of rice are stuck to your stirring spoon, instead of banging it against the rim of your pot, tap the spoon on the side of your hand. It all adds up to an ethos of gentle patience. One wouldn't fluff up rice with a spoon to begin with because it will damage the kernels, Irene would argue. Use a fork or chopstick, dummy!

On the menu today is beef rendang, a kind of stew served at weddings and other celebrations; turmeric rice; acar timun, a warm, crunchy cucumber and carrot salad flavored with green and red chilis, mustard seeds, anise, pulverized shrimp, and a balanced blend of sugar, vinegar and salt; and for dessert kueh koci ― balls of grated, toasted coconut wrapped in a rice flour dough and steamed in a banana leaf.

We will be using the mortar and pestle a lot today to crush our ingredients. Our instructors prefer the word "massage." Even in the act of making our rendang paste, we are encouraged to do so gently, quietly.

The paste is added to oil over low heat. At this point, Irene recommends walking away ― folding your laundry, checking your email. Patience is king. Once the paste starts sticking slightly to the wok, water and beef slices are added. When that sauce reduces, we will add coconut cream, salt, palm sugar, asam keping (garcinia cambogia, for some sourness), and finely sliced turmeric and kaffir lime leaves, reserving some for garnish.

The rendang will take about 90 minutes. In the meantime we prepare our other dishes.

The heat is getting to the Americans. They can't follow instructions and keep asking for cold towels, smh.

Here, Zeera talks about what goes in our spicy cucumber salad (acar timun). At the market, Zeera noticed I liked the spicy curries, which is why she addresses me when talking about the chilis.

We begin making the turmeric rice by sauteeing garlic, ginger and turmeric in ghee, a kind of Indian butter, until aromatic, followed by lemongrass, pandan leaf, curry leaves and mustard seeds. Your nose will tell you when to add the basmati rice and water, in a 1:1 proportion, cooking for 7 minutes. The pot is covered by a banana leaf (for aroma). The leaf is covered by the pot lid, which is pressed down by an upside-down mortar to keep steam from escaping. No peeking.

We take off our shoes and carry our plates to the upstairs patio, where Kumar quietly asks the group, "Do you mind if I eat with my hands?" This is the traditional way a lot of Malays and Indians do it. I look over at the hedge-fund monsters and see four sneers reserved for those of lesser castes. At that point my path is clear ― I have never been so sure of anything in my life. Dipping four fingers into the rendang and bringing it to my mouth, I am filled with an intense sense of liberation. Then some rice. Then some beef and rice. Li follows suit. Kumar is too polite to show his delight. He is a born teacher. Leaning over and whispering gently, he says, "Take small scoops. Then fold your thumb into the palm of your hand and push out with your thumbnail." I try it. It works!

"It's harder than it looks," adds Li. She's right. The thumb-bending part doesn't come naturally. But it's fun and strangely emancipating. The Americans sit silently. "I don't like warm salads, but that's just me," says brother-in-law Roger, his plate untouched. They can't wait to get back to the Marriott. Six hours ago I wouldn't have thought it possible, but this is turning out to be the best day ever.

My landlord, Barry, wants to take me out for a late lunch, and he lives nearby, so he'll pick me up. Kumar buzzes away on his scooter. I love that guy. Li thanks me for my handwritten list of restaurant recommendations in Ipoh. She's headed up there in a few days. Our yellow LaZat aprons aren't included in the price, so I buy one and bid my farewells to Zeera, Irene, Ana and their staff. "Bye, guys!" I yell to the Jersey crew from the yard below, and I get into Barry's company car.

"What do you do for a living?"

"I have a business with my brother-in-law. We sell industrial chemicals like hydrofluoric acid. Stuff industries need. We make the body wash in your condo, too."

"It's good body wash. Frothy."

He takes a business call on the speaker. He and the caller are speaking Hokkien dialect with a few English words thrown in. Sounds like they sold a few tons of acid today. We zoom south down Malaysia's main expressway. It goes all the way from the Thai border to Singapore. Encountering a couple of toll booths, he presses a button in his car and the boom barriers lift up for us to pass.

We stop at a place called Loong Kee Bak Kut Teh, which specializes in, uh, bak kut teh! (pork bone tea). Barry says he's been coming here 20 years, and he's greeted warmly by the regulars.

As a Chinese Malaysian (half-Thai), Barry's observations about his homeland mirror those of the Chinese guys I met in Ipoh. From what I have observed, the Chinese here work hardest, always grinding, sending their kids to universities, thinking generations ahead. They don't say so explicitly, but there is a resentment toward the majority Malays, whom they see as getting preferential treatment in all sorts of matters ― business, housing, criminal law. He asks what I think about him sending his daughter to a U.S. university when she turns 18 in a couple years. I break the news to him that the admissions policies at Harvard and elsewhere are also based on reverse discrimination against straight-A Chinese. It follows you everywhere, bro. He nods as if he knew the answer.

Much of what Barry says seems to come out of a Make Malaysia Great Again playbook. Illegal immigration is the source of most of the nation's antisocial behavior, he hints. He expresses admiration for Singapore, where the rule of law is less flexible. We've been communicating on WhatsApp for the past five months (yeah, I book early). Nobody seems to use SMS over here because of the cost ― there's no such thing as "unlimited texts." He's pretty much the perfect Airbnb host, making you feel like you are the most important guest he's ever had. I ask him about his worst experiences with Airbnb and he shows me pictures of trash left behind by previous tenants. It was pretty funny.

A couple days later an envelope is slid under my door, containing a couple of cutesy postcards. One of the cards contains the inscription, "If I had a single flower for every time I think about you, I could walk forever in my garden."

And that, folks, is Malaysia.

But first things first. At 8 a.m. we all meet up at a market in Damansara, where we are greeted by Zeera, a funny, lovely hostess who grew up in Ipoh. We have a light breakfast of Indian puri and a variety of curries, including a hot white curry (who knew?), and we walk around the market, sampling the sweets and fruits, poking the fish and chatting up the vendors. What follows is a kind of lengthy discussion of Malaysian spices ― feel free to skip; it's important to me. At the beginning of the video, Zeera's in the middle of talking about galangal, one of the ingredients I was pondering at Big Tree Foot when I was trying to figure out what lent citrusy bitterness to laksa. It's all beginning to come together. Spices discussed are:

Galangal

Turmeric (root and leaf)

Kafir lime leaf

Curry leaf

Lemongrass

Laksa leaf (Vietnamese coriander)

Torch flower

Pandan leaf

At the Damansara market, little kids wait for their morning puri.

I used to be freaked out by rambutan because of its spiky rind, but it's super-easy to peel by hand and tastes kinda like canned peaches. Yum.

We pile into a van and are driven to the cooking house in a kampong (village) at the edge of the city, where we are greeted by Irene, the heart and soul of LaZat Cooking. It is from her that I learn the conceptual underpinnings of cooking Malaysian-style ― 1) the importance of flame control (low and slow), 2) the importance of using cooking oil, because no other agent can produce the aromas you seek in as timely a manner and 3) something that surprised me ― the Malaysian chef works as silently (and gently) as possible. If bits of rice are stuck to your stirring spoon, instead of banging it against the rim of your pot, tap the spoon on the side of your hand. It all adds up to an ethos of gentle patience. One wouldn't fluff up rice with a spoon to begin with because it will damage the kernels, Irene would argue. Use a fork or chopstick, dummy!

On the menu today is beef rendang, a kind of stew served at weddings and other celebrations; turmeric rice; acar timun, a warm, crunchy cucumber and carrot salad flavored with green and red chilis, mustard seeds, anise, pulverized shrimp, and a balanced blend of sugar, vinegar and salt; and for dessert kueh koci ― balls of grated, toasted coconut wrapped in a rice flour dough and steamed in a banana leaf.

We will be using the mortar and pestle a lot today to crush our ingredients. Our instructors prefer the word "massage." Even in the act of making our rendang paste, we are encouraged to do so gently, quietly.

The paste is added to oil over low heat. At this point, Irene recommends walking away ― folding your laundry, checking your email. Patience is king. Once the paste starts sticking slightly to the wok, water and beef slices are added. When that sauce reduces, we will add coconut cream, salt, palm sugar, asam keping (garcinia cambogia, for some sourness), and finely sliced turmeric and kaffir lime leaves, reserving some for garnish.

The rendang will take about 90 minutes. In the meantime we prepare our other dishes.

The heat is getting to the Americans. They can't follow instructions and keep asking for cold towels, smh.

Here, Zeera talks about what goes in our spicy cucumber salad (acar timun). At the market, Zeera noticed I liked the spicy curries, which is why she addresses me when talking about the chilis.

We begin making the turmeric rice by sauteeing garlic, ginger and turmeric in ghee, a kind of Indian butter, until aromatic, followed by lemongrass, pandan leaf, curry leaves and mustard seeds. Your nose will tell you when to add the basmati rice and water, in a 1:1 proportion, cooking for 7 minutes. The pot is covered by a banana leaf (for aroma). The leaf is covered by the pot lid, which is pressed down by an upside-down mortar to keep steam from escaping. No peeking.

|

| The turmeric rice is done. All you have to do now is fish out the pandan leaf knot and lemongrass stalk. |

|

| My plating job. To make the rice this shape, we press it into a coconut half shell and flip it over. The rendang is also in a coconut shell. |

|

| Everything is delicious. Clockwise from top are kueh koci, turmeric rice, acar timun and beef rendang. |

"It's harder than it looks," adds Li. She's right. The thumb-bending part doesn't come naturally. But it's fun and strangely emancipating. The Americans sit silently. "I don't like warm salads, but that's just me," says brother-in-law Roger, his plate untouched. They can't wait to get back to the Marriott. Six hours ago I wouldn't have thought it possible, but this is turning out to be the best day ever.

My landlord, Barry, wants to take me out for a late lunch, and he lives nearby, so he'll pick me up. Kumar buzzes away on his scooter. I love that guy. Li thanks me for my handwritten list of restaurant recommendations in Ipoh. She's headed up there in a few days. Our yellow LaZat aprons aren't included in the price, so I buy one and bid my farewells to Zeera, Irene, Ana and their staff. "Bye, guys!" I yell to the Jersey crew from the yard below, and I get into Barry's company car.

"What do you do for a living?"

"I have a business with my brother-in-law. We sell industrial chemicals like hydrofluoric acid. Stuff industries need. We make the body wash in your condo, too."

"It's good body wash. Frothy."

He takes a business call on the speaker. He and the caller are speaking Hokkien dialect with a few English words thrown in. Sounds like they sold a few tons of acid today. We zoom south down Malaysia's main expressway. It goes all the way from the Thai border to Singapore. Encountering a couple of toll booths, he presses a button in his car and the boom barriers lift up for us to pass.

We stop at a place called Loong Kee Bak Kut Teh, which specializes in, uh, bak kut teh! (pork bone tea). Barry says he's been coming here 20 years, and he's greeted warmly by the regulars.

|

| I love the fried bean curd skin floating around in this insanely complex pork broth. |

As a Chinese Malaysian (half-Thai), Barry's observations about his homeland mirror those of the Chinese guys I met in Ipoh. From what I have observed, the Chinese here work hardest, always grinding, sending their kids to universities, thinking generations ahead. They don't say so explicitly, but there is a resentment toward the majority Malays, whom they see as getting preferential treatment in all sorts of matters ― business, housing, criminal law. He asks what I think about him sending his daughter to a U.S. university when she turns 18 in a couple years. I break the news to him that the admissions policies at Harvard and elsewhere are also based on reverse discrimination against straight-A Chinese. It follows you everywhere, bro. He nods as if he knew the answer.

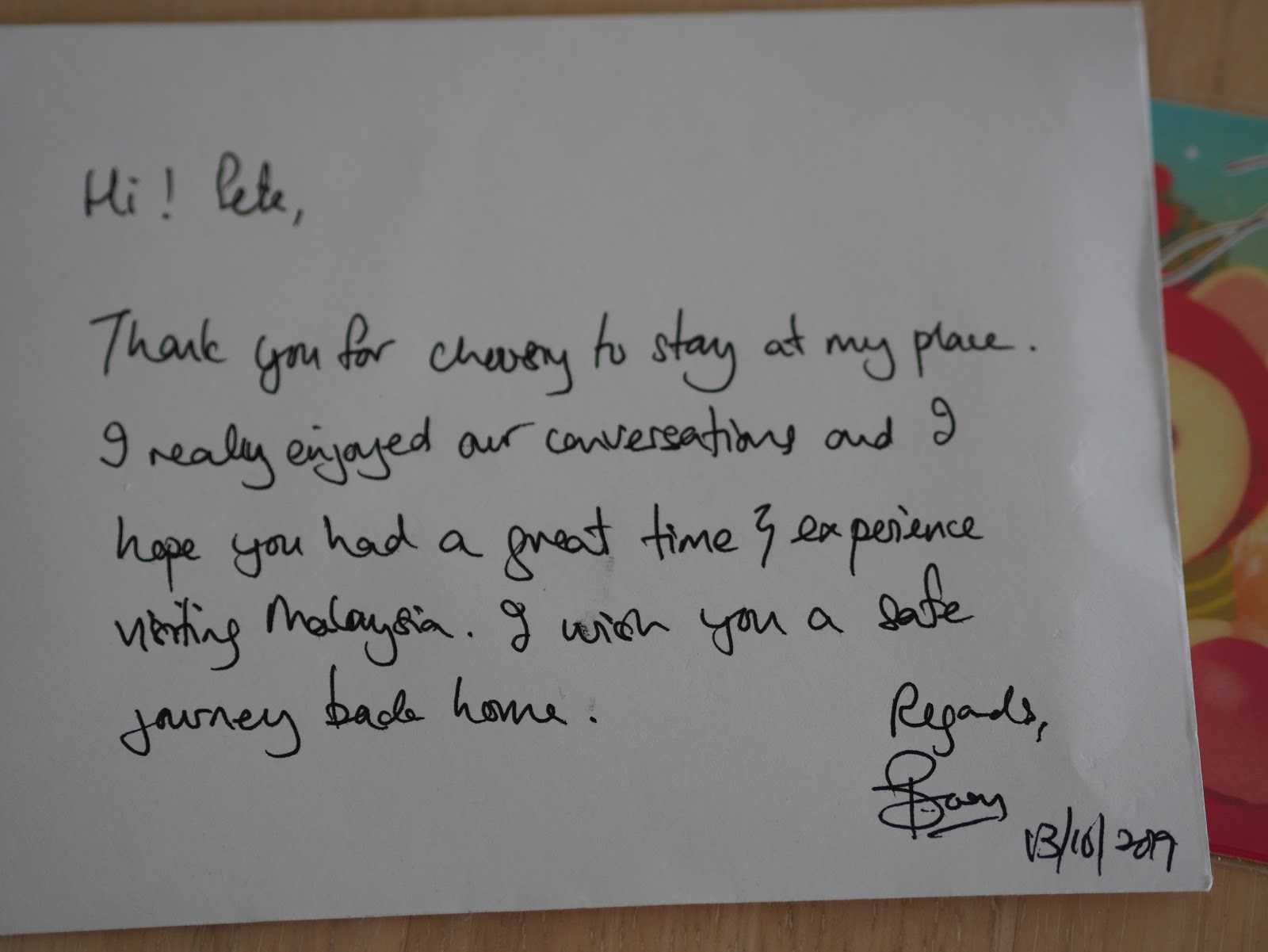

Much of what Barry says seems to come out of a Make Malaysia Great Again playbook. Illegal immigration is the source of most of the nation's antisocial behavior, he hints. He expresses admiration for Singapore, where the rule of law is less flexible. We've been communicating on WhatsApp for the past five months (yeah, I book early). Nobody seems to use SMS over here because of the cost ― there's no such thing as "unlimited texts." He's pretty much the perfect Airbnb host, making you feel like you are the most important guest he's ever had. I ask him about his worst experiences with Airbnb and he shows me pictures of trash left behind by previous tenants. It was pretty funny.

A couple days later an envelope is slid under my door, containing a couple of cutesy postcards. One of the cards contains the inscription, "If I had a single flower for every time I think about you, I could walk forever in my garden."

And that, folks, is Malaysia.

Comments

Post a Comment